Preface: I wrote this series of articles to show how to get excellent results in body work with simple tools. It's intended to be a guide for the novice body worker trying to save money, and covers only surface preparation prior to painting. Not everybody can afford the big air compressor and special tools associated with this kind of work for what may be a one time job. I'm into my third full restoration and sixth paint job, and still prefer to keep it simple. I hope this little piece will help someone because any day I can help someone is a good day for both of us. Click here to see all articles in this series

- John D. Weimer

Mixing Automotive Paint

There are some real fancy ways of mixing paint, but we're going to bring it down to the basics which is all we really need. There are little dippers with a hole in the bottom you put paint in and time how long it takes to run out. There are painter's measuring cups with so many scales and increments you can't figure out how to use them, and hard telling what other methods. Then there are good old Folgers coffee cans, clean 'em out good and let them dry completely.

Mixing ratios: The basecoat I'm using here is mixed 2 parts paint to 1 part reducer (thinner) so I measured a can from the top of that bottom lip and put 3 marks one inch apart.

Then I use a center punch or nail and hammer to punch little dings in the side of the can on the top two marks so I can see the exact measurements and ratios inside the can while mixing.

You can also mark a paint stick and have it standing in the container as your scale while you are mixing. If you want to mix less use a smaller can or substitute 1/4" or 1/2" for 1" per part as you measure the container. Sometimes you'll run across what looks like a screwy ratio in the instructions because they never use a fraction of a unit in the measuring process. For instance: Your paint requires reducer and hardener in the mix. The ratios given may be something like 6 parts paint, 2 parts reducer, 1 part hardener to 6 parts unreduced paint. They will never have anything like 3 parts paint, 1 part reducer, 1/2 part hardener to 3 parts unreduced paint.

Now for that portion that says "1 part hardener to 6 parts unreduced paint". The way we are measuring it just means "1 part hardener", forget the "to 6 parts unreduced paint", our mix will come out right because of the method of mixing we are using. The can with 4 marks is marked incorrectly for what I'm doing and I discarded it, but you've got the idea about easy measuring.

You are quite likely to find some terms you are unfamiliar with in the instructions, such as:

Pot life: Like Cheech may say to Chong, "Man this Pot Life is great! Gimme another hit." No, really, 'pot life' refers to how long the paint is usable. If it has no hardener the instructions will likely say "Pot life indefinite", which means you could seal it up in the can, mixed or unmixed, and keep it as long as you wish. If the paint requires hardener it will likely say something like, "Pot life 6 hours". In that case you have 6 hours to use all the mixed paint or dump it out and clean up the gun. Never pour even the tiniest amount of paint with hardener added back into the container because it will activate all the paint it comes in contact with, which is all of it in the can. Even 1/2 ounce of hardener will eventually activate an entire gallon of paint.

Flash time, or time to flash: This is the minimum amount of time you must wait before applying another coat of paint. Longer is OK, even better; shorter is asking for runs or curtains in the paint. I like to extend flash time by at least a third then look at the paint and see if it looks right. If it doesn't, I'll wait longer. Any place that still looks damp isn't ready.

Tape free: The minimum amount of time you must wait before applying masking tape over the freshly painted coat. This is important when masking out an area to create a two-tone paint job. I like to at least double this time, then decide for myself if it really is ready to tape. This is also a good indicator as to minimum time before removing masking tape, but I treat this the same, at least double the time, even wait a couple of hours longer.

Time to delivery: The time it takes the finished paint job to cure to a state where it can be handled or used safely; it is by no means fully cured at this stage. If you have items such as trim and door handles to re-install I suggest waiting no less than 3 days and I'll wait a week. You can work these items sooner than that safely, but "I prefer to wait 'till that paint is harder than the hammers of Hell."

Some every important terms that can spell disaster to all the work we've done (and, you'll never see them in the instructions) are in the next segments.

Automotive Paint Systems

A paint system consists of all the matched components to go from primer to finish and the containers in the photo are self explanatory.

The basecoat in this Sherwin Williams 4th Dimension system requires no hardener which is a big advantage. That being you have up to 7 days to apply the clear coat without first scuffing the base to make it stick. I didn't need that window, but had the temperature dropped or the humidity gotten too high for a period of days after the basecoat was on I may have.

This is one of the "economy" paint systems, how economical depends on the colors you choose. It is quite easy to use, the instructions are simple, the times between each step of the job are reasonable, it lays out good, and works very well in the environment I was working in. There are other so called "low priced" paint systems, DuPont's Nason series being but one of them.

Economy versus expensive systems: The price of a paint system has little or nothing to do with how well it works, quality of color, fineness of finish, or durability. The biggest factor is speed of usage in a controlled environment such as a paint booth. Speed is the last priority on the list in an uncontrolled environment.

Body shops sell time, that is their bread and butter, the mark-up on materials is minimal by comparison. The big shops that have a mixing station and professionally designed and built paint booth have specialists in every area of body repair. The "mechanics" get the car first. They do the necessary frame tweaks, panel replacements, and repairs.

Next a painter who may or may not be the finish shooter applies the primer, and sends it out to the prep boys. They sand the primer, where and if it needs it, and mask the vehicle in readiness for the finish coat(s). Some of the primers they use require no additional work before applying the finish coat. These guys are fast and efficient and do little masking with tape and paper like we have to.

Door jambs are "masked" with an expensive round sponge tape that blocks air flow and doesn't create a line where it's used. Most of the body masking is done with a very thin plastic sheet that holds to the body by static cling and is taped along the line to be painted.

Then, it goes into the paint booth and the main "shooter" who earns and average of $1,200.00 per week, so the company wants him turning out as many jobs as possible and thus the working speed and expense of the paint systems they use. When he's finished it goes back to the prep boys for final detailing of the finish, then to the body mechanics for installation of glass, trim, interior, just whatever that job requires to be finished.

Painting in Your Garage

But, here's what can happen in a home carport. I think its just as good as what I described above!

There are several factors that can contribute to making a finish coat a dismal failure. Up to this point you've learned how to avoid all of them other than blowing dust and bugs. Bugs will be there or they won't, its just the luck of the draw, but you know how to deal with them. If you noticed the floor in the pictures taken after sanding was finished, you've seen it is washed as clean as it can be made; this helps the dust situation.

Here are 3 more things that can ruin a job and how to avoid them.

1) Your air hose: If the air hose gets into your work it can wipe out a small area plumb down into the primer and cost you a day in dry time and repairing the damage. Any time you must shoot with the gun above chest high drape the air hose over your shoulder, across your back, pull it snug with the other hand, and hold it behind you. You will inadvertently turn the same direction most of the time while going from side to side on the car and this will cause the hose to start looping. When you see this, disconnect the gun and straighten the hose. If you let it go and a loop flops into your work I can guarantee you'll throw an unmitigated cuss fit even if you have never uttered an obscenity in your life. "You'll be flopping around on the floor, kicking and screaming like a Wal-Mart brat."

2) Solvent pop: This is the result of painting over uncured primer and may not show up for weeks. Our new paints are about as porous as plastic and that's zip, zero, nada. Nothing gets past it without a lot of force. I won't paint over a large primer coat that has cured for less than a week nor spot primer any sooner than 24 hours. This usually doesn't cost any time because my slow schedule doesn't allow painting any quicker than that.

Here's the scenario: You prime an area and have ants in your pants until you can finish sand it. The paint gun is standing by with the mixture in a can ready to stir, dump in and shoot. You knock out the job in record time and it looks great, the best you've ever done, and it looks great...for a few days, weeks, or even months. Then, one day, you're washing your car and you feel something strange underhand. You dry it off, look, and see nothing wrong.

Wait a minute, what was that? You get down at a low angle, move around to shift the light and "What's that?" It's Solvent Pop: thousands of tiny pinpoint bubbles in your paint job. How did they get there? In your rush to get the color coat on you didn't let the solvents escape from the primer.

In other words, you didn't let it cure. Those solvents were trapped by the paint, weeped out under it, and the first time the car sat out in the hot sun, the solvents changed to gas, expanded, and blew bubbles under the paint. It could be worse. It could actually lift big sections of paint in which case it would soon peel off.

3) Lift: This is much akin to solvent pop, but now usually happens between the basecoat and clear coat. You've seen it a hundred times on mid '80's and later cars. There are two things that can cause it: clearcoating before the basecoat has cured enough; and, clearcoating when the basecoat has cured too much. In re-painting it can be avoided two ways, wait a little longer for the basecoat to dry or scuff the basecoat with a Scotchbrite pad before clearcoating. Read the instructions on the paint to know when you are in the clearcoating window. It can vary from a few hours up to a week.

Orange peel, dry spray, and several other problems are the result of not following the instructions for the paint. You don't just buy some paint and some thinner, dump it together and shoot any more. Now-a-days you buy a paint system and use it precisely as the instructions state.

Enjoy Your Handywork

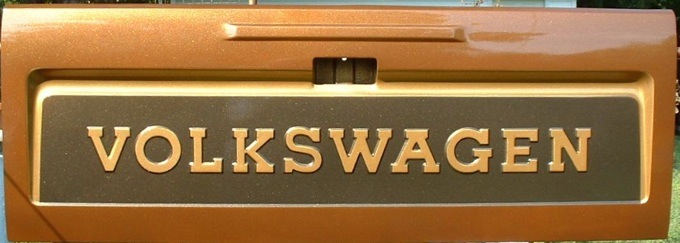

It was a quiet celebration, Miller time was. As I relaxed at last there in the shade with a cold Miller High Life in my hand, my gaze was fixed upon, of all things, a 1981 Volkswagen Rabbit Diesel Pickup tailgate hanging in the sun where my yard swing should be. My eyes played over the glittering copper and gold glinting in the sun like an Aztec idol with millions of tiny copper flakes winking and glittering from the dark, nearly black, pewter accent panel with the near perfect hand cut letters.

Countless days of toil and drudgery faded into nothingness as the final coat of paint dried, shrunk, and cured, becoming smoother with very minute. Another Miller and another smoke. I hadn't relaxed like this in days. Why?

Because today was the culmination of a labor of love which has been especially stressful. The success of my labors depending entirely on a discipline for which I had to constantly remind myself, "It doesn't have to be slick, just wet, it'll lay out later". I must have repeated that phrase to myself a thousand times doing this final round of painting today.

But, today, there she was.

No drips, no runs, no errors. Three shallow curtains in the clear coat with the largest being 1-3/4" long and 3/4" high and simple to repair. All lines between the colors are as if cut with a knife, and no discernible division can be felt between one color and another. There is no dividing line between jamming the doors and painting the truck.

Miracle of miracles, there are no bugs in the paint. A few specs of dust from the wind getting up while shooting, but the color sanding will remove them in a jiffy. All conditions except the last two are controllable by techniques outlined beforehand. This is the most nearly perfect finish I have ever put on a vehicle and I couldn't keep my eyes off it as it cured and laid out.

Painted and looking great, all the better for doing it yourself

Now, just a few tips:

- The paint doesn't have to go on slick, just wet looking; it will 'lay out' (the surface will blend to a finish) later as it cures.

- Just because a paint gun's instructions say it will hold a full quart doesn't mean you have to put a full quart in it. Fill it to within about 2" of the top so none can get out the cup vent and drip onto your finish coat. After a shot sharply upward or downward check the paint cup for runs down the side. If you see any it means your cup gasket is not sealing properly. Unless paint is simply running out, grab a rag and keep shooting, and start wiping the run off making sure not enough accumulates to drip onto your work. The next time you fill the gun, check the fit of the lid on a top cup gun or if you are using a bottom cup with a clamp type closure just turn the cup around 180 degrees and that may fix the problem.

- When removing masking tape always wait well past the flash time, maybe 4 times longer, and try to pull the tape back over itself at a 45 degree or lower angle. That will cause the paint bridging from it to the finish to be cut instead of trying to lift.

All that's left now is color sanding, buffing, pin striping, and undercoating. That is, other than installing the hundreds of parts and components that have been overhauled, cleaned, painted, lubricated, refurbished, made ready for use and stored in the spare room of our basement for over a year.

She'll be a 1981 VW diesel pickup with the turbo-diesel engine and 5-speed tranny along with the dashboard and most of the interior and some exterior parts from an 1984 VW Jetta. There is also a little bit of VW GTI and Dodge Neon thrown into the mix also. She will be quite unique, nothing like her ever before, and never again.

Thanks to Pete Cummins she already has a name. Pete christened her the "JETTUP": a Volkswagen pickup built with the heart of a Volkswagen Jetta.

The Dreaded Orange Peel

Remember what I just said about orange peel and following instructions? Well, here is a fine example of orange peel caused by not following instructions. The instructions for the clear coat said to apply 2 coats. When I got 2 coats on everything I had about 1/2 cup of paint left and didn't want to waste it so, I gave the hood and outer tailgate a third coat.

When I jambed the hood with 2 coats of clear it was horizontal and came out slick as a button. While painting the tailgate I put 2 coats on the inside, 3 on the outside. The outside orange peeled, and the inside is "slicker than greased owl manure". The entire rest of the truck got only two coats of clear and is much smoother than either of these items; in fact I'm not going to sand or buff the dark color along the bottom, it doesn't need it at all.

Ready for this? I screwed up again!

The peel on the hood was so bad I decided to stick sand it with 600 grit wet paper to knock it down quick, then hand sand with 1500, and buff it.

Big Mistake!

That 600 put sand scratch in so deep neither 1500 nor buffing could fix that mess. You absolutely can not remove sand scratch with a buffer and finishing compound; it will only widen and deepen the scratch. I had to trash the rags I'd been using because they had 600 grit abrasive in them from wiping the hood down, wash the hood to make sure it was off of it, and spur the buffing pad to rid it of the "gravel" it had accumulated. Next I stick sanded with 1200 wet paper followed with 1500 hand sanding and buffed it again. Some 600 scratch was still there. Back on it with the 1500 followed by the buffer again and that got it passable.

What I should have done can be explained in pictures 1 and 2, and is the way I did it on the tailgate. This is pertaining to color sanding flawed or orange peeled surfaces. Wet stick sand with no courser than 1200 paper to about the stage you see in picture 1, notice there is still quite a bit of pitting from the orange peel showing. Wash the area with plain water to rid it of any 1200 grit left behind and wet hand sand it with 1500 to the stage you see in picture 2. Any remaining pits no larger than half the size of a pin head will be diminished by the buffer to a state that they are hardly noticeable. If, however you want a glass like show car finish every bit of pit and every flaw must be sanded completely out before buffing.

The hood buffed out pretty good, not perfection, but not half bad for a carport wannabe body beater. There is an art to buffing. As you use the buffer keep the following tips in mind and you'll do OK. 3M # 0611 Imperial Micro-finishing compound and a wool buffing pad can't be beat for this job. You don't need an expensive buffer, if you never use one you'll never know the little difference between them and cheap ones anyway. Most all of them have 2 speeds, high for sanding, low for buffing.

Always buff at low speed, if you're on high speed and stay on one spot too long or make the wrong move things start happening real fast and you can ruin a job in the blink of an eye. Keep the buffer moving. We are removing paint with wet pumice and a fast moving pad. and the friction causes heat. Stay still too long and the heat will soften the paint, the pad will get hold of it and pull a chunk out; it's called "burning" the paint. Get on an edge wrong, the machine jerks in your hands and you have burned completely through the paint and into the primer before you know anything went wrong. So run the buffer on the low speed and give yourself that extra split second advantage.

Here's how to avoid problems while buffing:

- Wear old "trashed out" clothing. sometimes what that buffer slings on them simply won't wash out, ever.

- Shake up the compound and squirt some on the surface to be buffed, you'll catch on to how much pretty quick.

- Set the buff pad in the compound and smear it around a little, then start blipping the buffer switch and spreading the compound around the general area where you want it.

- Switch the buffer on low speed and start buffing somewhere away from any edges of the part you are working until you get the feel of the machine.

Don't force the buffer into the work, it's own weight is all the pressure it needs or should have. Notice that when you hold the main handle up the front of the pad tries to pull it to your left, handle down and the heel pulls it right; secondary handle down and the buffer pushes toward you, up and it pulls away. Make careful note of the relationship of handle movement to buffer reaction and what part of the pad is doing the work.

Now for the important part: When you approach an edge that is the "cut off" edge on your right hold the main handle up slightly, keep the right edge of the pad barely over and perpendicular to that edge with the toe edge of the pad spinning off the cut off edge. Never buff onto any edge, always buff off it. If that edge is sticking up like the fender bead on an MGB you'd use the same action except you'd keep the pad off that edge as much as possible. Letting the pad run across any sharp edge will buff all the paint off it in a twinkling. After some practice you'll be able to buff a complete tailgate, small trunk lid, or anything you can reach across without walking all around it. Just practice on a flat area using imaginary lines until you get the gist of it. Your buff pad should be at least very slightly damp, except for one instance explained later.

Now we are buffing right along and as the compound begins to dry you'll notice it beginning to vanish and a shine emerges. When this begins observe what is going on very carefully. Normally you just keep buffing until the compound is gone and the shine is there, but there is one warning sign to watch for. If you see a swirl or even a partial one in any part of the buff, compound or shine, stop immediately. Some drying, but damp, compound has gathered in a "knot" on the pad and has to be spurred off before proceeding. "Spurring the pad" is turning the buffer pad side up, turning it on, and dragging a straight slot screwdriver across the running pad.

The dried pumice and fur will fly so do it where you can make a big mess and it doesn't matter. In fact this is the best way to clean a wool buffing pad either when finished or before use. Washing them causes the wool to knot up on the ends and you have to spur them before use anyway. Don't worry about hurting the pad, I've used and spurred the same one for 15 years and It's still going strong, You should spur the pad any time the buffer sits idle for more than a couple of minutes.

This may be an exception to the damp pad rule above. I just discovered this today, the light was getting bad and I'm not sure it did all of what I think it did, but I think so. I really believe it worked. When buffing at this stage, with this compound, and this pad you'll usually get some light buffer swirl marks. Not like the one I mentioned before, it will be wide, these will be miniscule and uniform. There is a special fingered sponge pad and super fine compound 3M calls 'Finesse It' to remove this natural buffer swirl, but what I did today, by chance, just may remove natural swirl too.

My pad was dry, but uniform and didn't need to be spurred when I used it on the tailgate for the last time and it seemed to remove the swirl so I tried it on the hood and it looked like it worked there too. Maybe it did, I'll find out later. Something else that will hide swirl and eliminate surface haze is 3M # 05977 pink Fill 'n Glaze. This stuff has no wax, silicone, Teflon, or any "wonder drugs", is hand applied and buffed, works very easily, and very well. After buffing my tailgate had a surface haze in an area where in diffused light the color was subdued. I wiped on, wiped off some pink Fill 'n Glaze on about a three inch circle and it looked like it just lit up. It works well on any car finish.

Removing swirl marks from the painted hood with a random orbit buffer

I got good light on the hood and tailgate today and there is no swirl. It also dawned on me what is causing the nearly imperceptible haze on the surface. It is buffing compound stuck in the paint from working it so soon after applying it, about 24 hours after. That's not a problem, left alone it will slowly be removed by successive washings, it can be re-buffed when the paint cures more, pink Fill 'n Glaze will fix it, maybe even a wax job will mask this minor situation. The reason I started color sanding and buffing so soon is if you let clear coat cure too long it gets so hard you can hardly sand it at all.

It's totally amazing how much these colors can change under varying lighting conditions. In this picture the side of the truck looks rather mundane and the dark at the bottom appears nearly black. In bright sunlight the colors show true and light up as they should. If you scroll back up to the tailgate and compare it with the hood you'll notice some subtle differences there too. Both pictures were taken in bright sunlight, but the tailgate hadn't been color sanded and buffed at that point, the paint was still nearly wet, and the orange peel mentioned earlier hadn't developed.

Paint Color Change Under Light

When choosing colors you'll usually have a definite color in mind, can get the number, and just buy your paint system with solid information. In this case I had three toning, paneling, and only general colors for building blocks. A must when choosing paint is to take the color cards or chip book outdoors in direct sunlight in order to see the true colors. The fluorescent lighting in stores will change some colors beyond recognition, especially metallics. Luck was with me when choosing these colors. The company, Sherwin Williams, had their colors on "decks" of cards with which I fanned out some choices, went outside, and chose these three. Being able to hold the three colors next to each other was a big advantage.

Pin Striping

Pin striping is the next consideration and there are several points to bear in mind.

First: You want to end up with accents, not distractions or a "hillbilly" motif.

Second: The pin striping should create a tie-in with the interior of the vehicle.

Third, and very important in this case: The tape must have the flexibility to conform with curves in the paint design. There are a dozen curves with the radius of a quarter in this job so the tape will have to be narrow, and I am currently researching tri-color designs only 1/8" wide.

We'll get into pin striping later as Fall is coming on and I want an ambient temperature of at least 80F to lend flexibility to the tape before applying it.

talking with a mechanic about this today...

need ideas

regular practice to make it perfect biro

jodoh

Want to leave a comment or ask the owner a question?

Sign in or register a new account — it's free